Part I: Munchkinlanders

“She would go mad; the world was nothing but water and want. If a frolic of elves scampered through the yard she would leap on them for company, for sex, for murder.”

In a May 1657 English court case, an alehouse keeper’s wife named Mary Combe was sued by her neighbors for a series of promiscuous activities she had undertaken over a six-month period.

The previous December, she’d stripped off her clothes and walked home from the tavern fully naked, propositioning all who walked by. The next week, she’d lay down in the middle of the main road, raised her skirts, and asked the men who passed to “make my husband a cuckold.” In March, she and three strangers had kept the neighborhood up by drunkenly singing and swearing into the wee hours of the night and then showing up still drunk to church the next day. The final straw came on March 29th, when she invited a neighboring man inside, locked the door, lifted her skirts, and said “Come, you rogue, look thee here what thou shall play withall.”

She is an icon and a legend and I don’t know what happened to her after the suit, but I think of her often, when people try and suggest dumb things about early modern peasants (no, a Sabrina Carpenter song would not make Mary Combe spontaneously combust, thank you, I think she would actually probably love Juno). Most recently, I thought of her when re-reading the first few chapters of Gregory Maguire’s 1995 134k F/F college AU Wizard of Oz fanfiction more colloquially known as Wicked.

If you have not read the book and are struggling to understand how Mary Combe’s story would possibly relate to the Cynthia Erivo/Ariana Grande film with the pink/green Mac & Cheese tie-in, let me assuage your fears. It doesn’t make sense to me either.

The last time I read this book, I was eleven. My sister and I would sandwich duets of For Good in between renditions of I’m Just Like You from Barbie’s The Princess and the Pauper. I spent more time dreaming about possibly one day studying at a refined institution like Shiz University and laughing at the dramatic irony of the novel than actually thinking about it.

Now, nearly a decade and a half later, I am twenty-four. I’ve read Judith Butler and Silvia Federici and Vincent Bevins. I have a litany of dumb little early modern court cases shoved into my brain. I also, unfortunately, am coming to terms with the fact that my entire life seems to have been a slow creep towards worldwide authoritarianism.

So when I read the first pages of Wicked, when I hear about the Clock of the Time Dragon, the overthrown regent, the beginnings of industrialization, Pleasure Churches vs Unionists, I am immediately thrown back into the early modern period. And of course, when I read about Elphaba’s mother, Melena, and the various affairs she has while high out of her mind on opium and alone at home, I think about Mary Combe.

When I was eleven, I agreed with the residents of Munchkinland that Elphaba and Nessarose’s oddities were probably because their mother was a whore or a drug addict. Now that I’m twenty four, it seems incredibly medieval and Munchkin-like of me to view the things that make them different as curses. After all – without the girls being othered, as they are – they would not grow into their power quite so easily.

“It didn’t escape her attention, however, that both Melena and Frex had believed uncompromisingly that they would have a boy. Frex was the seventh son of a seventh son, and to add to that powerful equation, he was descended from six ministers in a row. Whatever child of either (or any) sex could dare follow in so auspicious a line? Perhaps, thought Nanny, little green Elphaba chose her own sex, and her own color, and to hell with her parents.”

There’s something in this quote, this logic behind Nanny’s thinking that pulls at a string inside of me connected to all sorts of philosophy about feminism and bodily autonomy and choice. While most unwanted babies are not born green, many are born into similar situations to Elphaba, with absent fathers and unmaternal mothers. What does it mean to assume that having a girl instead of a boy is a curse, a breaking of paternal lineage? What does it mean to imply that daughters are punishments for the promiscuity of their mothers?

The first thing you learn when you re-read Wicked as an adult is that if you’re agreeing with the Ozians at large on something, you’re probably in the wrong. Maguire makes that clear in Part 1; Elphaba is born a green teethy monster for the same reason she is born a girl. Because that’s who she was meant to be. To hell with tradition and supposition and convention.

After all, did Mary Combe really deserve all that?

Part II: Gillikin

Gregory Maguire is a gay man. I should mention that straight off the bat. His 2004 marriage to his husband Andy Newman was one of the first same-sex marriages ever performed in Massachusetts. If Wicked came out in 1995, that means he was writing it at the tail end of the AIDS crisis.

Once you know that context, it coats the Shiz University section of the novel with a very queer sheen. Galinda gushes over Elphaba’s beauty, despite her greenness. She’s entrancing and exotic, her hair is black silk and coffee spun into threads, her green lanky limbs making her like a rare flower. Boq’s friends Crope and Tibbett are metropolitan, flamboyant, and always together, which makes them quite the gay little couple. Madame Morrible makes a comment at one point about the girls living in a “little womb, a tight little nest, girl with girl.” Then there’s whatever goes on in the Philosophy Club, which is a cross between a sex dungeon, a drag show and a performance of Cabaret.

But that’s subtext. I could go on about subtext in various pieces of media where there is in fact very little queerness to be found – hell, I’ve done it about Jane Eyre. The difference between that and Wicked is that Wicked is not merely interested in being gay via subtext but being queer via text. For a quick reminder on the distinction between the two, I’ll leave that to bell hooks:

"Queer as not being about who you’re having sex with - that can be a dimension of it - but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live." - bell hooks, 2014

The most queer part of Part II of Wicked comes in the arc surrounding Doctor Dillamond and the Animals. While his kin are systematically being stripped of their rights, Dillamond feverishly searches for something, anything, to prove his — for lack of a better word – humanity to those around him. He examines flesh samples, performs tests, and dives into ancient religious texts. Our motley crew of students help him along the way, working in secret to bring him the information he needs from libraries he no longer has access to.

“Doctor Dillamond wants to authenticate the way our ancestors thought about this. The Wizard’s right to impose unjust laws may be better challenged if we know how the old codgers explained it to themselves.” - Elphaba

Dillamond has made himself an exceptional example of his kind. He has risen against all odds to the rank of not only wealth but a respected position at Shiz University. Despite all this, he remains alone – the only Animal professor at Shiz we ever hear about. Even Galinda, who acts as the voice of oblivious privilege throughout the novel, can’t quite bring herself to care when Madame Morrible shoots dog whistles (pun not intended) at him about Animals needing to be seen and not heard.

He believes that if he can just conduct the right experiment or find the right research or cite the right chapter of the Oziad, his peers in wealth, prestige, and career will finally respect him. And the thing is, none of it matters. They kill him anyway. He could have produced any number of scientific, religious, or philosophical reasoning as to why he deserved to have the basic rights of any other soul in Oz and it would not have mattered, because when someone is set on (once again I’m lacking a better word here) dehumanizing the other, logic and reason no longer matters.

Dillamond is killed because he dares to speak out against the imprisonment and discrimination of his people. He is killed because he is able to sway others into being allies to the cause. But most importantly, he was killed because his very existence as a wealthy, educated Animal in a position of respect and power at Shiz University exists at odds with the transforming world around him.

There are allegories in the treatment of the Animals in Wicked to racism, to antisemitism, to homophobia, to ableism. We can think of their caging as equivalent to the Victorian banishment of the disabled and queer to asylums, the 1940s internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, the segregation of Jim Crow America, the apartheid of South Africa, and of course the Holocaust. I don’t think it is directly meant to be any one of those things, but rather to cause an American audience to think on all of them. The rounding up of one group of others is the prelude to the subjugation of all. How does that poem go again? First they came for the communists…

We can recall, from our outside knowledge of the Wizard of Oz, that part of this has to do with the fact that the Wizard has come to Oz from an incredibly eugenicist and Social Darwinist turn-of-the-century America and brought that to his reign, but it takes more than one person’s bad beliefs to strip a whole group of people — or in this case Animals — of their rights. Doctor Dillamond’s arc shows us that many Ozians were all too ready to jump at the chance to put Animals back in cages. They just needed someone’s permission to give in to their hatred.

I’m not going to point out the echoes of this that I see in our current political climate, both on the national and international stages. It’s so obvious I might as well be hitting you on the head with a bat labeled “every hot take on the election you’ve been forced to read on Twitter in the past few weeks.”

Instead, I will say that history is not a straight line. Rights and freedoms ebb and flow with the swinging of the political compass. Dillamond is a reminder that no amount of money and status and professional respect will save you – only the community you create around you can do that.

Dillamond’s story makes me think of Jean Baptiste Lully, a composer who was a favorite of Louis XIV for most of his reign despite his homosexuality being an open secret, only to be exiled in the latter years for his reign once the pendulum swung back towards religious authoritarianism. He makes me think of writer Stephanie Robinson’s beautiful script for Chevalier (2023) and the man who inspired the film – Black composer Joseph Bologne, who was a similar favorite of Marie Antoinette, only to be dismissed and imprisoned as the tides turned leading up to the French Revolution.

However, what the stories of these men have that Dillamond’s story does not is that they were able to survive beyond their initial disgraces because they did not isolate themselves from their fellow marginalized people. Lully spent his last years writing an opera about Achilles and Patroclus under the patronage of a similarly homosexual Duc de Vendome. Bologne led an all-black regiment against the monarchy that had once championed him during the French Revolution. They were able to do that because they sought community amongst their peers, rather than letting their exceptionalism isolate them. Dillamond dies alone because he is still, at the end of the day, seeking acceptance from his oppressors instead of his community.

I think Gregory Maguire, who spent the first decade of the AIDS crisis coming to terms with his sexuality while a professor at Simmons College might know a thing or two about learning that lesson himself.

Part III: City of Emeralds

“I do not listen to anyone who uses the word immoral,” said the Wizard. “In the young, it is ridiculous. In the old, it is sententious and reactionary and an early warning sign of apoplexy. In the middle-aged, who love and fear the idea of moral life the most, it is hypocritical.”

So a large industrial state is being ruled by a former quack/con-man/show-man who has gained his power by tapping into a culture of already existing fears of the other and dissatisfaction with the former political ruler. Fascism is approaching, and it’s time for Elphaba to learn the very first lesson from Timothy Snyder’s pamphlet “On Tyranny”: Do not obey in advance. Maybe, as we all go see Wicked (2024) this auspicious month, we should try to learn this lesson too.

Doctor Dillamond’s death is shortly followed by Elphaba, ever his protege, attempting to carry out his dying wish by bringing his research to the wonderful Wizard of Oz. She, like Dillamond, believes that if those in power could just read the right argument or see the right data, it would change what they believe to be true about the world.

When she finally gets an audience with the Wizard, she tries to appeal to his ego, his logic, and his sense of right and wrong. She assumes he has an interest in the pursuit of justice, as well as an ignorance on the rights of Animals. She keeps saying “if you please.”

The Wizard, of course, laughs in her face.

What Elphaba learns here, and what we should learn as well, is that we will not find salvation by supplicating ourselves to those causing our suffering. They know what they do. They simply do not care.

“I know of Doctor Dillamond and I know of his work… Derivative, unauthenticated, specious garbage. What you’d expect of an academic Animal. Predicated on shaky political notions. Empiricism, quackery, and tomfoolery. Cant, rant, and rhetoric… I know of his interests and findings. I know little of what you call his murder and I care less.”

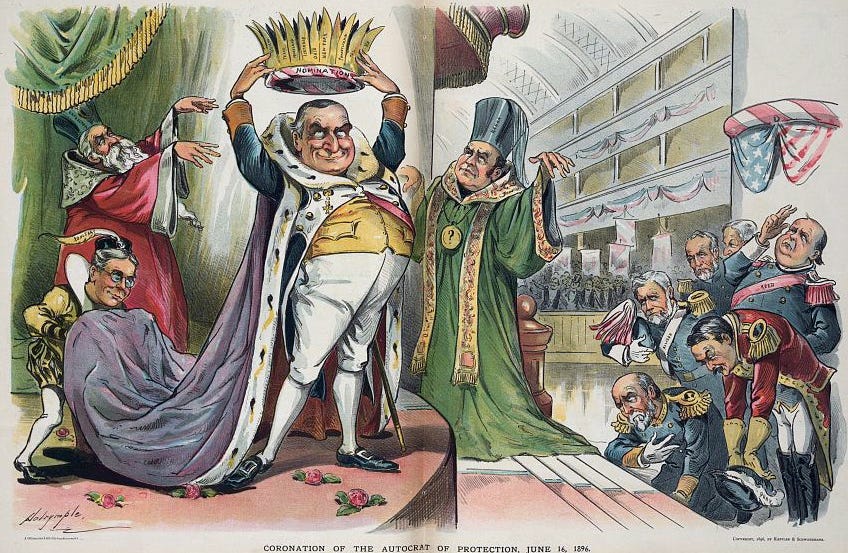

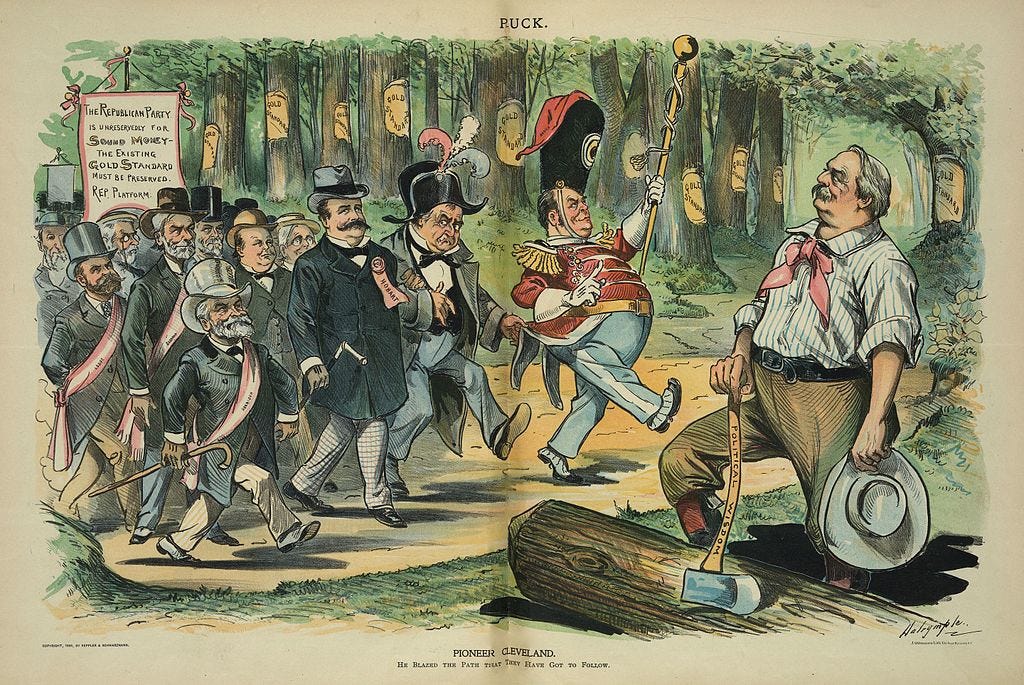

Much has been made of Frank L Baum’s original intentions when writing The Wizard of Oz. There have been discussions about his possible allusions to the contemporary arguments surrounding bimetallism, the 1896 presidential election, and the crisis over capital and poverty caused by industrialization at the time he wrote the book. The Wizard of Oz (1939) can be read as about many things of its time as well – The Great Depression, the rising global authoritarianism of the period, and FDR’s presidency just to name a few. I’ve already established how the AIDS crisis hangs over Wicked, and the 2004 musical’s composer Steven Schwartz, said much of the Wizard’s song Wonderful (especially the lyrics Is one a crusader or a ruthless invader? / It’s all in which label is able to persist) was influenced by the foreign policies of both Bush presidencies:

“[The Iraq War] was completely sold on misinformation and disinformation, that was propagated not just by our government, but frankly by [the British] government too. And also the demonization of Saddam Hussein as a justification for the war. Not that he wasn’t a bad guy, but the total black-and-white demonization obviously struck us as a part of the story.”

Maguire also joked of the former president that we should consider what the “W” in George W Bush stands for.

All that to say, when we consider how this story, this incredibly American fairytale, has evolved through its adaptation, and when we consider the timing of the 2024 adaptation, I cannot help but hope that this new Wicked, if director Jon Chu has been paying close attention to its predecessors, will have something to say about authoritarianism. Then again, as mentioned earlier, this is the adaptation with tie-in green and pink mac & cheeses so I’m not sure I should be putting all my eggs in the basket of radicalism stoked by the book.

However, as Schwartz would say, "We always knew the show was political… I don’t think you can watch the show and not pick up on it. I mean, unless you’re five. But even then, they’re taking in something about social justice.”

If it’s not clear, I see glimmers of the current moment in these stories. I see the fight for abortion rights in the story of Melena, of a society intent on punishing sexuality through forced birth of unwanted children. I see the stripping of rights of trans people and immigrants in this country in the story of Doctor Dillamond and the Animals. I see the brave youth movements of the past few years – whether that be for gun control or for gay rights or for Gaza – in Elphaba’s stand-off with the Wizard. I see myself, my loved ones, my generation, in the precipice that Elphaba stands on in the aftermath.

The intermission of Wicked the stage musical happens after this confrontation with the Wizard, as Elphaba and Glinda part ways during the song Defying Gravity. Jon Chu has confirmed that the film will cut off around the same point. In the book, Elphaba leaves Part III deciding she needs to become “something worse” in order to fight against the injustices of her time.

So with bated breath, and many thoughts crowding my head about the legacy of queerness and politics and art under the slow creep of fascism, I will leave those of you also thinking those thoughts with Elphaba’s parting words to Glinda–

“You’ll be alright…” She put her face against Glinda’s and kissed her. “Hold out, if you can,” she murmured, and kissed her again. “Hold out, my sweet.”

(And no, it is never specified what kind of kiss this is. God, I love you, Gregory Maguire).